Genome Editing: What’s the Big Deal?

At the same Beef Improvement Federation (BIF) meeting this year, I had a chance to watch a few presentations on the status of the use of genome editing (or gene editing) technologies in our industry.

Dr. Alison Van Eenennaam from UC Davis gave an overview of what is happening currently in our industry and if my memory serves me right, that sparked a debate in one of those presentations. The debate centered around whether we should be practicing genome editing, because that could decrease the diversity (a.k.a variation) within the traits.

Well…there are a lot of traits out there where we don’t see a lot of variation in and that was all done through conventional breeding. So, in that regard, no points would be awarded to using genome editing, nicknamed “precision breeding” as the sole cause for the lack of diversity that it could eventually create.

It has been almost 12 years since I handed a term paper in where I reviewed the use of genetic engineering and its promises to enhance mastitis resistance in livestock. A lot has changed since then: a new term (genome editing), a more precise technology (CRISPR) and I am now on a first-name basis with industry experts.

Before I got ahead of myself, I decided to contact Dr. Alison Van Eenennaam and have her answer some questions and clear up the air on the use of this new technology.

So, here you go, some questions and answers.

Genome Editing (or Gene Editing) Vs Genetic Engineering

Elisa Marques: Alison, my first question has to do with the meaning of the terms genome (or gene) editing vs genetic engineering. The public tends to pool those two terms together and thinks that we are playing semantics. How would the scientific community describe them?

Alison Van Eenennaam: In a nutshell, genetic engineering is the use of recombinant DNA –rDNA (foreign DNA)- into the genome of an animal (plant, crop or other species). We take foreign DNA (from different species), introduce it in another species and pray that it would stick somewhere in its genome. Once in there, that piece of foreign DNA is stable enough to be passed on to future generations. The result is often a phenotype that didn’t exist before in that species. We have examples of crops being resistant to pesticides. That’s genetic engineering.

With genome editing, we don’t introduce a recombinant DNA sequence. We perform precise cuts removing the unfavorable allele replacing it with the favorable allele from the same species.

Elisa Marques: So…random and praying vs precision and speed….

Alison Van Eenennaam: Correct. With genome editing, we can precisely target the site that we want modified. We have the knowledge of the genome site where we want the modification to be made. We make precise cuts in those regions and add the version of the gene – the allele – that is most desirable. These outcomes are analogous to those obtained with conventional breeding programs, and really only differ in the precision and speed with which the useful genetic variation can be introduced into the target breed.

The Status of Genome Editing in Livestock

Elisa Marques: At BIF, you talked about the polled project in Holstein. Can you tell us more about this project?

Alison Van Eenennaam: A company called Recombinetics took the polled DNA sequence found in Angus and introduced it into the genome of an originally horned Holstein animal.

Elisa Marques: If my memory serves right, that was successful.

Alison Van Eenennaam: Yes. Two hornless (polled) Holstein-cross bulls were produced. But now the FDA is considering regulating these animals as a drug which would mean they would want to see more data on whether or not the milk or meat originating from the genome edited animals is any different than from animals that have not been genome edited. Which means we have to wait a few more years to collect milk data on the offspring of the original genome edited bulls.

Elisa Marques: It sounds like the gene edited polled animals are being subjected to regulatory review differently than if crossbreeding were performed.

Alison Van Eenennaam: Correct. This would be no different than crossbreeding, except that we are only changing the sequence at a specific location.

Elisa Marques: Any other successful cases out there of using genome editing?

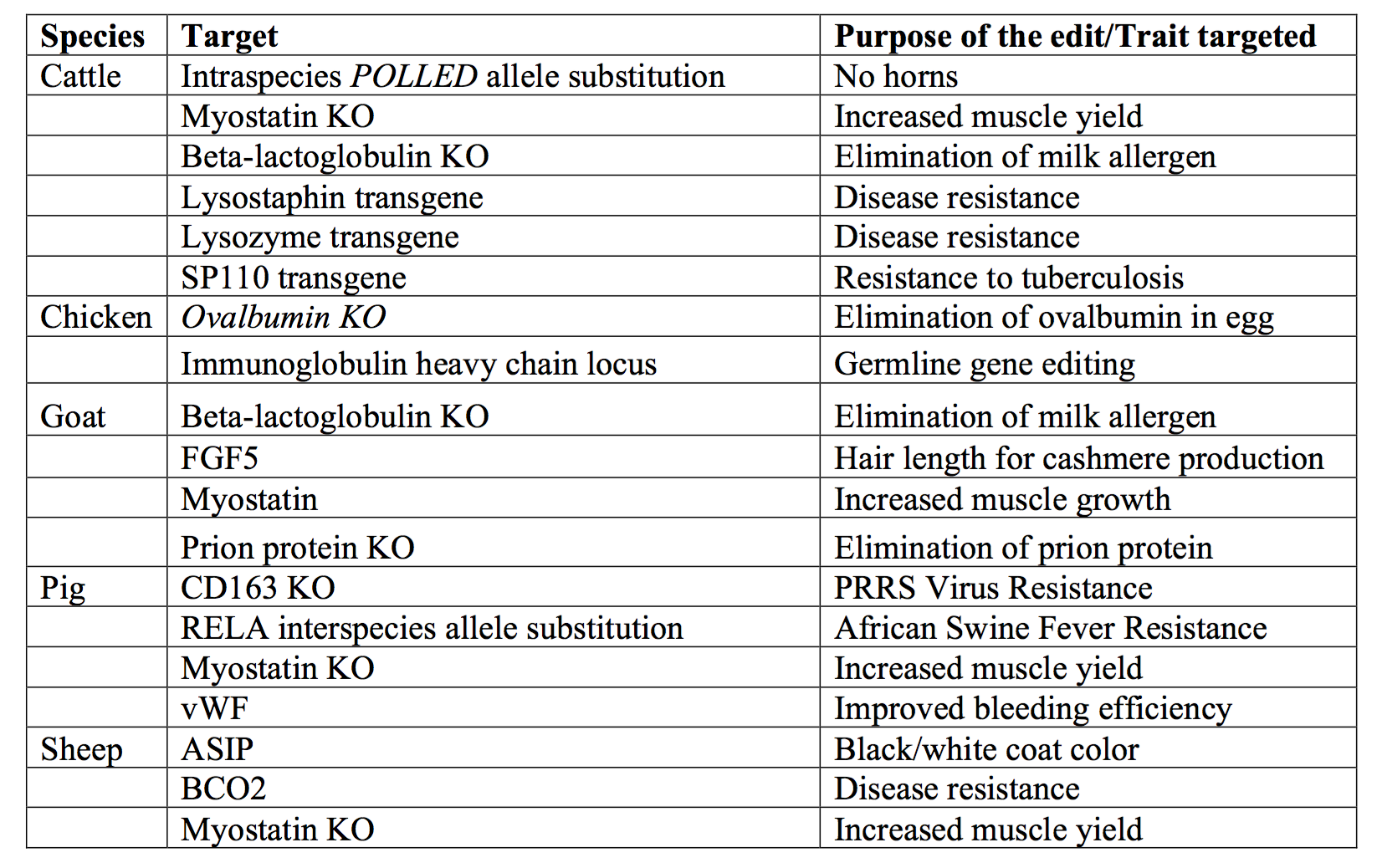

Alison Van Eenennaam: Yes. Quite a few. We have other cases in cattle and in other species like chicken, goat, pig and sheep.

Examples of successful gene edited agricultural applications in food animal species. KO = knock out or inactivation of gene function. Reproduced and modified from Van Eenennaam AL. 2017. Genetic modification of food animals. Curr Opin Biotechnol 44:27-34.

What does this mean for genomic selection and the future of animal breeding?

Elisa Marques: There are a lot of people that look at this sort of technology and say “Whoa, we just introduced genomics not too long ago and I am still trying to catch up on all of that.” And that’s immediately followed by “Does that mean I won’t need to buy genomic tests anymore?”

Alison Van Eenennaam: Absolutely not. Gene editing can bring in discrete genetic variation – like the polled allele at one gene. Most traits of economic importance and the ones for which we use genomics are controlled by thousands of genes, so we will still need genetic evaluation programs to get accurate genetic merit. Gene editing would complement, not replace traditional genetic improvement programs.

LEARN | TRANSFORM | EMPOWER

Join 1,000s of other AgBio Talent!

Subscribe to AgBio Insights!

Elisa Marques: In light of the current debate on the regulation surrounding genome editing, can you tell us how the FDA is interpreting genome editing?

Alison Van Eenennaam: In January 2017, the FDA revised the #187 Guidance for Industry and the new guidance defines all intentional DNA alterations in animals as “drugs” which is different from the 2009 Guidance. Basically, the FDA is now interpreting every intentionally-induced SNP or alteration to be a separate new animal drug and then subject to new animal drug approval requirements.

Elisa Marques: I see. Can anyone make comments on this draft?

Alison Van Eenennaam: Yes. Anyone can access the draft and submit comments up until Jun 19th, 2017. The link is: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FDA-2008-D-0394-0325. You need to go to that page and click “Comment Now” on the right side. There are several questions posted there asking for scientific evidence demonstrating that there are categories of intentional alterations of genomic DNA in animals that pose low to no significant risk.

If it helps anyone before commenting, I have a blog about my thoughts on this proposed regulation: http://biobeef.faculty.ucdavis.edu/2017/01/22/fda-seeks-public-comments-on-regulation-of-genetically-altered-animals/

Elisa Marques: Any other concerns about this draft other than what you just mentioned?

Alison Van Eenennaam: The other is the inconsistency in how the FDA is dealing with this matter compared to how they have dealt with similar issues on the plant side.

To quote a recent Nature article “The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has suggested that many plants whose genomes have been altered by a single DNA letter change should not need approval before being released in the field. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) contends that animals whose genomes have been similarly changed might have to go through a rigorous evaluation before being released onto the market.”

Elisa Marques: In terms of the benefits that these technologies – genetic engineering and genome editing – bring. What can you say?

Alison Van Eenennaam: There are a lot of potential benefits. First, both GE and genome editing are breeding methods that have the potential to help animal breeders achieve genetic progress.

If we think in terms of numbers here, the costs of disease are estimated to be 35-50% of turnover in developing countries and 17% in the developed world. Using genetic engineering or genome editing to bring in useful genetic variation such as disease resistance to viruses would be one way to help address this disease burden.

Infectious diseases have major negative effects on poultry and livestock production, both in terms of economics and animal welfare. Improving animal health using genetics has the added benefit of reducing the use of antibiotics and other medicinal treatments to treat sick animals.

Another potential use of genome editing would be on repairing the multitude of genetic defects like curly calf associated with pedigreed livestock populations.

Elisa Marques: It sounds to me that by focusing on the health-related benefits of the technology, such as the possibility of reducing the use of antibiotics, could be a way to convince the FDA of its benefits.

Alison Van Eenennaam: The way the regulation is written at the current time – ALL genome edits would have to go through mandatory FDA premarket regulatory evaluation. This can take several years, irrespective of the trait being targeted. And that is really the problem with the proposed regulation. It is triggered by “intentional” DNA alterations and not the attributes of the resulting animal. Some edits, like the hornless Holstein example, have exactly the same DNA sequence as exists in hornless breeds like Angus. In this case, there does not seem to be a good science-based rationale for treating these animals as a drug.

Elisa Marques: Any final comments?

Alison Van Eenennaam: While animal breeders will continue to make progress using whatever technologies and methods are legally available to them, it makes little sense to impede their access to safe breeding methods in the absence of a demonstrated risk. It is the innovation equivalent of tying the breeders’ hands behind their backs. Slowing down progress in animal breeding programs comes with a very high opportunity cost given the projected global increase in demand for milk, meat and eggs.

Elisa Marques: Thanks Alison.

Alison Van Eenennaam: You’re welcome.

What about you? Any thoughts and concerns about the use of this technology?

About the Author Elisa Marques

An advocate for lifelong learning. A self-admitted textbook collector. I have been traveling around the globe since the tender age of 16 and have lived in 3 different countries. Some say that the 90's cartoon character "Carmen SanDiego" was loosely based on me, but who knows. I am a nerd at heart with a huge passion for science, marketing and teaching.

Related Posts

When Less is More: Lessons from the Livestock Genomics Industry

Selection Indexes: If you are not in this business to make money, then good luck with your hobby.

3 Reglas de Oro para un Programa de Mejoramiento Genético Libre de Estrés

3 Golden Rules for a Stress-Free Genetic Improvement Program

How to Develop AgriGenomics Products And Get The Best Prices

The Future of the Breed Associations

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.